vol. u i\o,

June 10, ion

282-4337

Point park

The new beach access area in Pine

Point has been completed after a

year of work. The area, known as

Snowberry Ocean View Park in hon-

or of an amusement park that once

stood next to the Lighthouse Inn,

includes a new walkway, wood-

framed seating area, water foun-

tain, bicycle rack, split-rail fence,

sidewalks, crosswalks and narrower

traffic lanes to allow visitors bet-

ter access to the beach. Last week

Community Services added the fin-

ishing touch to the new park with a

sign outside the entrance.

__________________!

(Courtesy image)

Town is

rich in

village

history

First in a series on the villages of Scarbor-

ough. Next week: Pine Point.

By Dan Aceto

Staff Writer

When the town of Scarborough celebrated

its 350th anniversary in 2008, Bruce

Thurlow wasted no time preparing for the

next big celebration.

Inspired by a book that chronicled the

town’s history, “Scarborough at 350:

Linking the Past to the Present,” Thurlow

embarked on a yearlong project to preserve

memories he and other residents shared

growing up in the town’s many villages.

Thurlow said he took on the project so

others might enjoy and learn from their

experiences at the next landmark birthday

event.

This spring, with help from fellow

resident Mary Pickard of the Scarborough

Historical Society, Thurlow completed his

journey back in time by recording group

interviews with residents who grew up

in the villages of Pine Point, Prouts Neck,

Oak Hill, Pleasant Hill, Blue Point, Higgins

Beach, Spurwink, North Scarborough and

I hinstan.

More than ■!() residents shared their

photographs, memories and insight of the

town’s development and life from the 1930s

to today.

“I had the idea that 50 to 100 years

from now people may do another birthday

party and I wanted something that could

be accessed easily, with people talking

comfortably about these years when

Villages—————————

Continued from page 1

Scarborough really became Scarborough,”

said Thurlow, who grew up in Pine Point.

“I felt like a Huck Fin growing up and I

think that’s true for a lot of folks living in

different areas back then and my reason

for leaving this legacy is just that – because

we lived it.”

Although the villages may have been

miles apart, Thurlow and Pickard were

amazed by the many similarities residents

shared growing up.

“One of the biggest things is that people

felt they had more freedom,” Pickard said.

“If a child went to a house, that mother or

father was their mother or father. Houses

were never locked up, there were always

keys in a car and other parents even felt

free to discipline other children.”

Thurlow said many of the villages were

localized because they were separated

by the marsh and transportation was

impractical on a regular basis.

He said many residents remembered the

day-to-day adventures of growing up, such

as playing familiar games or having to walk

or occasionally hitchhike long distances to

school. Surprisingly, there were even small

gangs, Thurlow said.

“It was not uncommon for us ‘crickers’ to

have a gang to deal with the Tuller’ people

living in Blue Point,” Thurlow said with

a laugh. Thurlow said there was no road

in the 1930s, but a hill separated the two

villages and they were constant rivals.

For many, life was simpler with fewer

distractions than today, Pickard said.

“One of other themes was that everyone

said they were ‘poorish,’ but had a lot of

fun,” Pickard said. “Although they may

have been poor they didn’t know because

life was rich in neighborhood relationships

and they always had something to eat.”

Another topic of interest was the different

jobs children held. They joined nearly 300

clammers at Pine Point and worked in the

budding tourist industry at Prouts Neck

and other villages.

“A lot of people used to come by train

to resorts in Pine Point, Higgins, Prouts

Neck,” Pickard said. “They would get off,

arrive for summer and be met with horse-

drawn carriages.”

Many residents remembered the vast

amount of farmland and the dramatic

change brought about by housing

developments, Interstate 295 and increased

tourism.

“The roadways really opened

Scarborough,” Pickard said. “Some

residents estimated that 90 percent of the

farms became housing developments.”

Pickard said she and Thurlow became

interested in the villages in part through

a 2009 grant from the Maine Community

Heritage Project that included a $7,500

stipend for equipment at the historical

society. The grant allowed the historical

society to archive information online about

prominent people and places around town

and members worked with the library to

help gifted and talented students study

town history.

“The experience has been very successful

up to this point,” Pickard said.

Although a lot has changed in Scarborough

the past 80 years, memories are as clear as

day for those who lived in the 1930s, said

Thurlow.

“The thing that was great about being

in the audience, was that we would have

three to six people in a group who would

come in and chat with us and we would ask

one or two questions and then they would

just take off and talk about growing up,”

Thurlow said. “We wanted them to pretend

they were just sitting around the kitchen

table and talking.”

Staff Writer Dan Aceto can be reached at

282-4337, ext. 237.

Clams were core of Pine Point community

First in a series on the villages of Scarborough. Next

week: Blue Point.

By Dan Aceto

Staff Writer

For Don Googins and other residents of Scarborough

who grew up in Pine Point during the 1930s, clamming

wasn’t just a summertime activity. It was a way of life.

“Boys were born with a clam rake in their hand and

girls with a knife for cutting clams,” Googins said.

Earlier this year, Googins, along with fellow Pine Point

residents, Lenny Douglass, William Bayley and Bruce

Thurlow, shared their memories growing up in the

seaside section of town for an archival interview that

chronicles the history of Scarborough’s villages from the

1930s.

The project was spearheaded by residents Thurlow and

Mary Pickard, volunteers at the Historical Society, so

others could look back on the time “when Scarborough

At left, a 1951 photo of Pine Point Pier. The construction, right, of a new pier will be completed in June at Pine

Point. (Courtesy photo/Dan Aceto photo)

became Scarborough.” clamming,” Thurlow said. “Almost everybody down there

If you ask any resident, they’ll tell you Scarborough’s cut clams.”

history begins with the snap and crack of a clamshell.

“Pine Point was basically a cottage industry of §ee PINE POINT, page 6

Pine Point

Continued from page 1

And that meant everyone.

“As kids, I remember we’d have a barrel

of clams that we would have to cut

and shell before we’d go out and play,”

Douglass said.

Although opening a clam with a knife

may seem like a dangerous task for

youngsters, it was customary for children

to be involved in the day-to-day activity,

including helping knit “heads” or small

wooden planks for lobster traps.

Many young Pine Point residents,

including Googins, even turned a good

profit.

“Growing up that’s how we made money.

I remember I had about $1,500,” Googins

said.

The industry was such a fabric of the

community, Googins said, that even local

factories such as Snow’s and Thurston and

Bayley’s regularly employed residents to

shuck clams in their own homes.

“We didn’t have Social Security back

then, but everybody could cut clams at

home for extra added income,” Googins

said. “We had a big tray in the kitchen

and we would all go out and cut clams

and throw the clamshells in the avenue.

If I had to make an estimate, I’d say every

other house was cutting clams.”

Snow’s, one of the largest factories in

Pine Point for processing clams, was

built in 1921 and nationally distributed

“Scarboro” clams in chowders, pickled or

“soused” and other varieties. Luckily the

product wasn’t very hard to sell.

“The soft-shell clam was very, very

famous for a long time,” Thurlow said. “My

father used to say there would be no Pine

“It’s sad how much it’s

changed, but I remember

all the great times I had

growing up.”

– Bruce Thurlow

Point if it weren’t for clam shells.”

Though the flats were primarily used

for digging, Thurlow said also they served

another purpose.

“At low tide it was a source of income,

at high tide it was a source of swimming,”

Thurlow said with a laugh.

Although clamming used to be a vital

commercial industry for Pine Point,

Thurlow said the tide has changed.

“What used to be is not true anymore,”

Thurlow said. “Now there are very few

diggers and only certain sections are open.

In the old days, that was not true at all.

You could dig anywhere and you could

even dig without a license.”

Thurlow said stricter state regulations

and sanctions on where people could

dig and cut clams caused the industry

to gradually decline in the late 1960s

and 1970s. By the 1980s and 1990s, the

industry was a shadow of its former self,

said Thurlow.

“It’s sad how much it’s changed, but

I remember all the great times I had

growing up,” Thurlow said.

And just like the many clamshells

scattered along the banks of its shores,

memories of Pine Point are equally

Mary Pickard and Bruce Thurlow interviewed residents of Scarborough from the

different villages in town. Thurlow, who grew up in Pine Point during the 1930s

said he decided to do the project so the town would be able to look back on the

recorded interviews at its next landmark birthday celebration. (Dan Aceto photo)

bountiful.

From fishing and ice-skating at Kennis

Pool to movies and other recreational

activities at the local fire bam, many

residents enjoyed social gatherings

afforded by the quaint neighborhood.

Pine Point’s children were educated at

a one-room schoolhouse, another defining

characteristic of the village.

Originally built on land next to the fire

station, the schoolhouse served the needs

of all children in the area with one teacher

for about 50 students. Many students

assisted the teacher with basic tasks

such as helping mimeograph documents

and other less glamorous jobs, such as

cleaning the outhouse.

While some of the students’ duties were

See PINE POINT, page 7

Pine Point—————————–

Continued from page 6

less than glamorous, the view at the

school was to die for, Thurlow said. “It

looked right out on the ocean, talk about

being distracted.”

For many, the commute to school, was

made even easier by an alternate route

through the woods, known as “the rabbit

run.

Life changed with a paved road and

increased transportation in the 1950s, and

children soon were bused to Blue Point

School.

During World War II, American troops

also constructed trenches along the beach

of Pine Point.

“Every night we had to be in before 5,

and all the soldiers would patrol the beach

with German shepherd dogs,” Googins

said.

In the years after the war, the trenches

would be used for a very different purpose.

“We used to build huts and make a little

clubhouse out of it,” Bayley said.

Bayley will never forget returning home

during a particularly violent storm and

passing the Ocean Spray Motel.

“I heard a horrific noise and I looked

out at that big three-story motel. The roof

came right off and landed in the parking

lot,” Bailey said. “I ran over thinking I’ll

go over help somebody, but nobody was

hurt.”

Another form of supplemental income

for residents was renting space in their

homes to visitors Thurlow said.

“It was common for people to come up

in the summer and stay with a family,”

Thurlow said.

Before World War II, many local

residents and visitors also frequented

popular shore dinner houses for affordable

seaside meals at popular places such as

Snow’s Clam

Bake Dinners as

it stood in 1924.

Snow’s factory,

built in 1921,

was a major dis-

tributor of the

famous “Scar-

boro dam.”

(Courtesy photo)

the Pillsbury House, Waldren Hotel and

other local favorites, he said.

As the automobile industry slowly began

to replace trains, visitors stopped lodging

at residents’ homes and traveled to

different areas.

For Thurlow, the greatest change at Pine

Point has been the loss of community he

and others felt growing up in what was

once a fairly remote area of town.

“Pine Point now has become sort of a

resort area. It’s very expensive and a lot

of people that used to live there can’t

anymore,” Thurlow said. “Many people

that live in Pine Point are in business or

tourists that come to motels. And what we

have now is that people don’t necessarily

know each other. The changes from back

then to today are good not bad, but the

quaintness is not there.”

Don Googins

and his son

Dana proudly

display their

catch after

coming back

from a clam-

ming expedi-

tion in the

1970s. (Cour-

tesy photo)

Staff Writer Dan Aceto can be reached at

282-4337, ext. 237.

Proud of their ‘Hiller’ heritage

Residents of Blue

Point share stories

of the village

Second in a series on the villages of

Scarborough. Next week: Dunstan.

By Dan Aceto

Staff Writer

They were known as ‘Hillers,’ and in the

village of Blue Point during the 1930s,

they meant business.

“When I was a little kid you didn’t go to

the crick (Pine Point) without a gang, and

the crick people didn’t come to the hill

without a gang,” Lenny Douglass said.

It wouldn’t take long however, before a

strong sense of community would develop

between the once rival villages.

This year, Douglass, and fellow

Scarborough residents, Tim Downs and

Kirk Barrett, recounted memories growing

up in Blue Point for an archival interview

that focused on the different villages that

make up the town of Scarborough.

The project was spearheaded by

Bruce Thurlow and Mary Pickard of

the Scarborough Historical Society, as a

means of chronicling life from the 1930s to

the present and give residents a historical

reference look back upon at the town’s

next landmark birthday celebration.

Although they may have had their

differences at times, the villages of Blue

Point and Pine Point were unified by one

thing – the firehouse.

“That was the thing that melded us

together, both the adults and the kids,”

Douglass said.

Built in 1914 on Pine Point, the

firehouse served the entire town

of Scarborough and relied on local

volunteers to help protect the community.

Because many residents of Blue Point and

Pine Point were involved in the clamming

industry, many of those who heeded the

call of duty were local clam diggers who

worked during winter at Snow’s Factory

to help can and distribute clams. The

firehouse and factory helped bring the

villages together in a very unique way.

“There was a whistle built at the factory

that signaled the workers where to go in

an emergency,” Thurlow said. “It operated

on the steam that made the food and it

became a way of integrating the guys at

Pine Point and Blue Point.”

For many, that sense of community

brought on by the clamming industry was

See BLUE POINT, page 6

Helen Perley, second from right, displays her circus of mice to a group of children.

Perley, who lived on Seaveys Landing Road in Blue Point, bred white mice and

other small animals nationally for use in laboratories. (Courtesy photo)

Blue Point

Continued from page 1

instilled at a very young age.

“I started digging clams at 6 and then commercially

when I was 12,” Barrett said. “We’d have barrels of them

in the cellar where we would cut them.”

Downs agreed and said many area youth wouldn’t wait

long before spending their earnings.

“I grew up digging clams,” Downs said. “We dug clams

during the day and then partied at Old Orchard Beach at

night. Everybody cruised the strip with old cars. It was

like the movie, “American Graffiti,” that’s exactly the way

it was.”

There was another way for local youth to earn money,

however, and it was something a bit more bizarre.

“Back then we did whatever we could to make money,”

Downs said. ‘We’d sell all kinds of animals and snakes to

Helen Perley,” Downs said.

Perley, who lived off Seavey’s Landing Road in Blue

Point, bought, sold and bred mice and other animals to

be used in testing laboratories nationwide, including

Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor. When children would

come across anything slithering, slimy or just downright

odd, they knew it would have a safe, or relatively secure,

home at Perley’s White Animal Farm.

And what was the going rate for a fresh catch? Why, 15

cents per inch of course.

Perley got her start in the business after her son

brought home two white rats as house pets. For

“company,” Perley bought two female rats and “soon

the brood grew to be over 10,000,” according to a book

entitled “Mrs. Perley’s Peoples.” At her peak in the 1950s,

Perley harbored more than 33,000 animals at her home

in Blue Point, including her favorite, a skunk, which she

learned how keep as a pet.

With more than 30,000 animals, Perley needed all the

SEALCOATING

SPECIAL!

THROUGH JULY 16th

Additional discounts

for condominiums and

BLUE ROCK

STONE CENTER

^multi-home communities!

Prnf-prt- vmir invpcfmpnt Kv ofWHna ■>

Westbrook

737 Sorina Street

A postcard of the Lookaway Inn in Blue Point in the early-1900s. The inn was later purchased by the Volun-

teers of America, a faith-based human services organization that converted it to a home for orphaned chil-

dren. The inn was located on Snow Street, near where the overpass to Pine Point is today. (Courtesy photo)

help she could get.

“One of my jobs growing up was to clean out the cages,”

Barrett said. “I sold my fair share of snakes as well.”

Despite the lucrative profit afforded by the sale of small

rodents and reptiles, for Downs and other children in

the area, the odor upon entering the White Animal Farm

could be a bit overbearing at times.

“You couldn’t breathe in that house, there was no air,”

Downs said. “I never liked to go in because you always

knew there was something loose in there. Everything

moved.”

Even with an extra pair of hands, some animals simply

could not be contained.

“I remember going down Pine Point Road one day and

looking out seeing my friend poking at something with

a stick,” Downs said. “When I got closer I saw it was a

snake and I knew it wasn’t native to the area, so we

called the police to come and get it.”

As the cruiser pulled up and assessed the situation, the

officer didn’t quite know what to expect.

“The cop said, Svhy did they call me? They know I hate

snakes.’” Downs said. “I thought it might be a cobra, it

was at least eight feet long. When I said that he almost

had, “the big one,”’ Downs said with a laugh.

In an effort to remove the snake as hastily as possible.

Downs said he assisted the officer by opening the lid of

the cage for the animal and promptly shutting it after it

slithered in. After all was said and done, he knew there

was only place the snake could have possibly come from.

“Helen Perley,” he said.

Not even a week later, the snake was on the loose again

and this time, it wouldn’t be so lucky.

“It went to Bruce Turner’s house and his wife cut it to

pieces,” Downs said with a snipping motion.

Perley did more than just provide housing for

animals, however, and even trained mice to do tricks

at a small circus she built for children to enjoy inside

her house. Perley was multi-talented as well. In a book

that celebrated the 350th anniversary of the town of

Scarborough, Fred Snow, former owner of Snow’s Factory,

said she was the best clam digger in town.

With their hard earned coins in hand, many children

in the area spent their time hanging out at the local

variety store, Whitten’s.

“That was what the whole town centered around as far

as the village,” Downs said.

Located across the road from Jasper Street, near the

baseball field and chinch, the store sold a variety of

things that included candy and ice cream; a popular

See BLUE POINT, page 7

Blue Point

Continued from page 6

favorite for many youth in the area.

“I remember the first time they had ice

cream, it was a nickel for a cone and the

line of kids went all the way past Harold

Snow’s. I don’t know where they all came

from,” Downs said with a laugh.

Another local gathering place for

residents was a wooded area with a small

clearing behind Blue Point Church, known

as the Eagles Nest. The area, originally

settled by Native Americans, was home

to clambake dinners and other informal

gatherings for families and children in the

area up until the 1960s. Aside from being

home to many clamshells, there were a

plethora of Native American artifacts and

arrowheads to be found.

“I was like Tom Sawyer, down there,”

Barrett said. “There was always

something to discover.”

When youth weren’t digging for treasure,

there was always the local swimming spot

at nearby Jasper Street.

“It would actually dam up at the end of

Jasper Street and there was a pond that

we used to skate at night and behind the

church, too,” Downs said.

Another distinctive landmark in the

area was the Lookaway Inn. Established

as a hotel in the early 1900s, the building

was later bought by a religious group

known as Volunteers of America, which

operated the building as a home for

orphans.

Like Pine Point, another distinctive

feature of Blue Point was the one-room

schoolhouse. Located at the corner of Pine

Point Road and Jasper Street, the school

housed approximately 25 students in the

village from the early 1800’s until the

construction of the new Blue Point School

in 1965, and was converted into a house.

Another landmark of the area is Blue

Point Church, built in 1878. It served

residents until 1951 when the decision

was made to build a brick church. The

former building was converted into a

house.

As an influx of people from out of state

moved to Scarborough over the years, and

the demand for housing increased, the

landscape that surrounded Blue Point

changed dramatically.

“It used to all be pasture. It’s interesting

to see the metamorphosis that’s taken

place,” Barrett said. “You used to be able

to see the ocean.”

For Barrett, the development of the area

has contributed to the loss of community

he and others enjoyed as children.

“There isn’t a village anymore. It’s all

gone away,” Barrett said. “You used to be

able to walk up and down the road and

wave to everybody.”

Staff Writer Dan Aceto can be reached at

282-4337, ext. 237.

32R3V35I MORTGAGE

[ ” rv~5g3~| Learn more about the loan without payments

A crowd

gathered at

the Eagle’s

Nest in

Blue Point

during

the early

1900s.

The area,

which was

home to

clambake

dinners

and other

informal

gather-

ings, was

a popular

hangout

for resi-

dents in

the com-

munity

until the

1960s.

(Courtesy

photo)

Vol. 17 No. 9

July 8, 2011

282-4337

Dunstan defined community

Third in a series on the villages

of Scarborough. Next week: North

Scarborough.

By Dan Aceto

Staff Writer

With three convenient stores, several

gas stations, school, fire department,

pharmacy, post office, shore dinner houses,

barbershop and other businesses, the

village of Dunstan had all the amenities of

a bustling town in the 1930s.

But for Sarah Matteau and other

residents who grew up then, Dunstan,

most importantly, was home.

“It was pretty much my world,” Matteau

said. “We didn’t have to go anywhere else

for anything and hardly ever went to Oak

Hill. Going to Portland was like going to

Boston today and going to Boston was like

going to New York. It’s hard to believe

this small area could encompass so many

businesses at one time.”

Matteau, along with other residents,

shared memories of growing up in

the village community for an archival

interview that chronicles the development

of Scarborough.

The project was spearheaded by Bruce

Thurlow and Mary Pickard of the

Historical Society so others can look

back during the town’s next landmark

anniversary celebration.

The foundation of Dunstan village life

was a strong sense of community.

“You knew all your neighbors and knew

the people that ran the businesses and

everyone was friendly. It was a safe place

to be,” Matteau said. “We probably knew

too much about everybody,” she added

with a laugh.

Although Dunstan more than catered to

needs of local residents, the area served

tourists as well: It was home to a variety

of upscale local shore dinner houses such

as the Wayland, Normandy, Moulton

House and Marshview. The experience

was something to behold, Matteau said.

‘You didn’t just go in for a half-hour

and eat. It took several hours and several

courses,” Matteau said. “And they all

seemed to thrive.”

From steamed and fried clams to boiled

lobster and everything in between, the

shore dinners provided some of the best

local seafood in town for residents and

visitors. And for $2 a plate, the price

wasn’t too bad either.

See DUNSTAN, page 2

Elm trees line Route

1 in a 1950s-era

photograph of

Dunstan village. In

1966, a fire burned

the local pharmacy,

grocery store and

post office. The Dairy

Corner, a popu-

lar hangout today

and years ago, was

formerly a Texaco

gas station. (Courtesy

photo/Dan Aceto photo)

Dunstan

Continued from page 1

One of the longest lasting shore dinner

establishments was not in Dunstan,

but just beyond the town line in Saco.

Cascades, which opened in 1929, was a

popular destination and offered lodging

and food for weary travelers who arrived

by train.

The restaurant regularly employed

residents of Dunstan as waiters,

waitresses and kitchen staff until it closed

several years ago. Matteau and others

remember the establishment not only as a

restaurant but a piece of history.

“It was a very sad day for a lot of people

when they took that place down,” Matteau

said.

Thurlow attributed the decline of

shore dinner houses and tourism to the

popularity of automobiles in the 1950s

and less use of the rail system.

“Dunstan had once been a thriving

and very populous place,” Thurlow said.

“Although there is still the route that

connects Portland to Boston somewhat,

there are no longer any shore dinners and

the huge cabin industry has been replaced

by motels.”

Transportation also enabled residents to

have greater freedom. The construction of

Pine Point Road across the marsh in the

late 1950s would soon bridge villages such

as Dunstan, Pine Point and Blue Point to

other areas of town.

Loss of shore dinner houses was not

the only dramatic change. In 1966, a fire

at Murray’s Pharmacy also engulfed the

local IGA grocery store and post office.

The destruction was an incredible loss for

the community, Matteau said.

“It was devastating to the area,”

Matteau said. “That was the pharmacy,

but it was also where many people

congregated in the morning for coffee and

doughnuts.”

The loss of the village center forced

residents to buy goods at more distant

locations in town, such as the Mammoth

Mart – now the location of Maine Medical

Center’s Orion Center in Scarborough

– and bigger grocery stores such as

Hannaford Bros, and Shaw’s.

The landscape of Dunstan also

changed after Dutch elm disease swept

through Maine in the late 1960s and

1970s and eradicated nearly all of the elm

trees that once lined Route 1.

“It was loaded with elm trees, it was

beautiful,” Matteau said. “There were a lot

of beautiful fields and wooded areas that

were turned into housing developments.

Today things are constantly changing, it’s

good, but you long for the old days.”

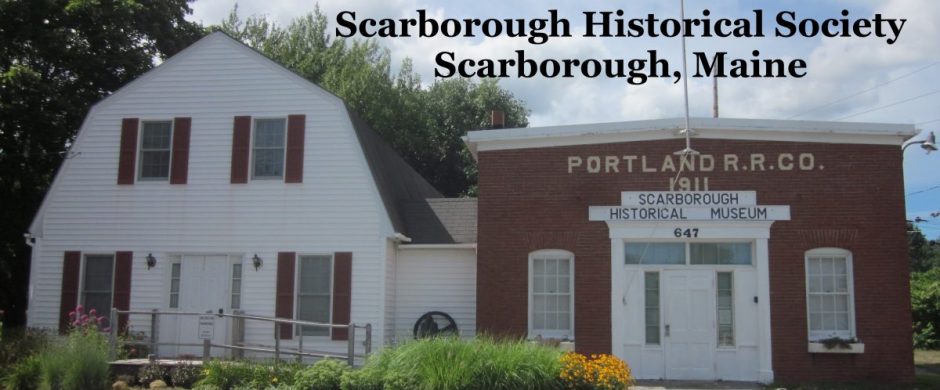

One distinctive landmark of the

Dunstan area, the historical society, has

a history all its own. Originally used as a

generator house for the trolley system in

town, the building supplied power until

1932 for one of the more unique forms of

transportation in town. The building was

The Marshview, one of many popular shore dinner houses in the Dunstan area,

was built in 1940. (Courtesy photo)

later renovated and became a museum in

1961.

Another landmark, Dunstan School

Restaurant, was built as a school in 1944

and replaced a smaller wooden school

built in 1925.

Among the popular gathering places

in town was the grange hall, where local

youth put on plays and hosted other

activities for residents. For men, different

filling stations around the village were

a favorite hangout. The Texaco station

is still in use today, although for a much

different reason: It’s now The Dairy

Corner.

One of the most popular attractions

for tourists and locals was Old Orchard

Beach.

“That was the place to go,” Matteau

said. “There was nothing like it, and you

felt safe down there. You had to go for

french fries and soft-serve ice cream.”

Dunstan’s neighborhoods have changed,

but Matteau’s memories are always close

at hand.

“For me, I can see all the houses and

know what they were and who lived in

them, so that kind of brings back the

changes that have been made,” Matteau

said. “It makes you realize, ‘wow this has

happened, they’re not there anymore,’ but

that also happens as you get older and I’m

sure my grandparents saw that, too. But

what I really miss most is knowing all my

neighbors.”

Staff Writer Dan Aceto can be reached at

282-4337, ext. 237.

s,z>— Scaraorougn Grange nan, ouitt in 1909, was a social gathering place for

residents of the village. The hall hosted a variety of events, including bean sup-

oers. dances, card games and the annual World’s Fair. At left, a sign that reads

Hfevs c*’ –sdandry Grange Hall” remains outside the the hail. Although the

feafl is sfl used, activity has declined in recent years. (Courtesy photo/Dan Aceto

Grange hall was the hub of ” 5 01

activity in North Scarborough

Fourth in a series on the villages of

Scarborough. Next week: Oak Hill.

By Dan Aceto

Staff Writer

It’s been more than 60 years since

Barbara Griffin served her first plate

of beans to local residents at North

Scarborough Grange Hall, but her

memories of the once-thriving village

center remain clear as day.

“That was the focal point in town,”

Griffin said. “It was huge.”

This year Griffin retold memories of

growing up in North Scarborough for an

archival interview that chronicles life

from the 1930s. Bruce Thurlow and Mary

Pickard of the Scarborough Historical

Society spearheaded the project to

use during the town’s next landmark

anniversary.

Life in the early to mid-1900s

centered on one establishment in North

Scarborough: The grange.

Built in 1909, the Patrons of Husbandry

Grange Hall was a social gathering place

in town for residents looking to chat, sit

down for a warm meal, dance or enjoy the

popular card game Whist.

The hall also was host to a slightly

larger event: The World’s Fair.

Held annually on the first Wednesday

of October, the fair was an opportunity

for local farmers and craftsmen to peddle

their wares and display their finest works

to residents.

Residents provided entertainment and

horse and dog races were held on dirt-

covered County Road.

The day held particular significance for

Griffin and other children.

“It was a huge event,” Griffin said. “I

remember as a kid school was closed that

day.”

The event was catered by grange

members who fed up to 500 people who

gathered in town for the day.

When the community wasn’t gathered

at the grange, another local favorite was

Sherman’s Store, now home to the Painted

Turtle Restaurant.

“That was where guys would play

Barbara Griffin

heaps a spoonful of

beans into a bowl

for hungry patrons

at North Scarbor-

ough Grange Hall.

Griffin has worked

at the hall since

1943. She contin-

ues to help orga-

nize bean suppers

and other events at

the hall. (Courtesy

photo)

checkers and card games,” Griffin said.

For children, activities such as sledding

on toboggans, ice skating and board games

were all popular community-building

experiences.

Some of the activities of yesteryear are

frowned upon today, such as lighting

bonfires.

“Today they wouldn’t let you do that, but

that’s what we used to do,” Griffin said.

“Those were the good old days,” she said

with a laugh.

Although the grange is still used today

to host bean suppers and other events, the

communal atmosphere is not the same as

See VILLAGE, page 5

Village——————-—

Continued from page 1

Griffin remembers.

“A lot of it today is that couples are

working and get home at 5:30 at night

and they’re expected to be involved in

children’s things at school so there’s no

time left to go to organizations (such as

the grange hall),” Griffin said. “It has

changed in that respect. Although today

the grange has things young people can

do, there hasn’t been as strong a draw as

there used to be.”

Griffin says fewer activities at the

grange also led to a decline in a sense of

community.

“Things like that kept people together,”

Griffin said. “Back then there was time

to spend with neighbors, but today

everybody is on the fast track. Your

neighbors were always there for you,

whatever emergency it was, they were

there.”

Thurlow attributes the decline of many

village communities to the development of

roadways. While they linked once distant

residents, they also allowed further

expansion of homes and businesses.

In North Scarborough, once dusty dirt

roads are now heavily traveled areas for

people outside town during their commute

to and from work.

“The traffic is big,” Griffin said. “It’s

bumper to bumper in the morning and

evening.”

The village, recognized for the fire

station at the intersection of County Road

and Saco Street, is now home to a busy

intersection that includes Lampron’s

Little Mart and First Stop Convenience

Store.

Although much has changed over time,

Griffin remembers the fun she and others

had growing up in the northern village.

“For me, growing up there was no other

place to go except the grange,” Griffin

said. “It was a different time, it was

simpler then.”

Staff Writer Dan Aceto can be reached at

282-4337, ext. 237.

Oak Hill has seen some changes

Fifth in a series on the villages of

Scarborough. Next week: Black Point.

By Dan Aceto

Staff Writer

Oak Hill, considered by many to be

the town center in Scarborough, has

grown steadily over the years to become

a burgeoning area for local commerce,

education and entertainment.

But Dick Foley and other residents who

grew up in the 1930s remember a time

when the town was different and life was

simpler.

“It was kind of an isolated life really,”

said Foley, 73. “Back then, Pine Point was

its own village, North Scarborough was

its own village and Oak Hill was its own

village. As a kid I hardly went anywhere

else.”

This year Foley and fellow Scarborough

resident Larry Jensen, 62, shared

memories of growing up in Oak Hill for

an archival interview that chronicles

the development of Scarborough.

Bruce Thurlow and Mary Pickard of

the Scarborough Historical Society

spearheaded the project.

‘Tor many years there was hardly

anything off Route 1 once you passed

Dunstan,” Thurlow said. “There were

Oak Hill Garage as it appeared in the 1920s. The area is now the site of the Scar-

borough Public Safety Building. (Courtesy photo)

no shopping centers behind where

McDonald’s is now.”

Family-owned businesses helped define

the early economic landscape of Oak Hill,

Thurlow said.

As a kid growing up in the 1940s, Foley

may have held one of the most desirable

jobs in town: He worked at his family’s ice

cream parlor.

Founded in 1948 by his father, Francis,

Foley’s was one of the first businesses to

define the area of Oak Hill in the mid-

1900s. Its nickel ice cream cones in the

1950s quickly earned the business a

glowing reputation.

“It was a pretty busy place,” Foley said.

Life at the ice cream parlor wasn’t all

sugarcoated, Foley admits.

See OAK HILL, page 2

Oak Hill——————————————–

Continued from page 1

“My first jobs included lugging water down to the store,

changing the trash barrels and washing the floors. I did

about every job in there,” Foley said. “I remember I used

to work until 9:30 at night on Sunday and then drive

back to Boston when I was in college.”

In 1963, Foley, his sister and brother took over the ice

cream parlor after purchasing the business from their

father for a down payment of $500 each.

The store continued to grow in popularity and served

more than 31 popular flavors to people near and far until

it closed in 1994.

Although the ice cream parlor was a local favorite,

several other landmark buildings also have come and

gone over the years, including Jensen’s father’s auto shop,

now the site of Amato’s at the Oak Hill intersection.

Across the street at the Bangor Savings Bank site was

another famous landmark, Dr. Benjamin Wentworth’s

house. One of the first physicians in town, Wentworth

also owned acres of farmland planted with olive trees

where the high school stands today.

One of the most dramatic changes to the area was

development of the school district.

Bessey Commons, now converted into apartments for

people 55 and older, was the first high school and often

the first place children from Scarborough’s many villages

had a chance to meet.

The former Oak Hill Grammar School also became

home to a familiar landmark: The Scarborough Economic

Development Corp.

The popularity of athletics in Scarborough made schools

a setting for town social events.

“Basketball games were a big thing in town, not only for

the kids playing, but the parents,” Thurlow said. “If you

didn’t get there early enough you didn’t get a seat.”

And after sporting events, there was only one place to

go: Mary and Bob’s restaurant.

“We used to love going to Mary and Bob’s, it was the

local high school restaurant and hangout,” Foley said.

“All the high school kids used to go there after basketball

i games. It was always fun.”

Although the restaurant closed in the 1960s, the land

is still used today and is home to St. Nicholas Episcopal

I Church on Route 1.

When teenagers weren’t participating in sports, regular

dances known as canteens were held each weekend at

town hall.

Other entertainment included the drive-in movie

theater, formerly located at the site of Memorial Park

See OAK HILL, page 5

Oak Hill——————————————-

Continued from page 2

behind Town Hall, performance plays at the Lions Club,

and the local town auction. Jensen recalls attending the

unique town event.

“I remember the things that didn’t sell went into what

was known as the ‘glory hole,’ and at the end of the

auction you could buy the entire glory hole. It would cost

about 50 to 75 dollars and take about three trucks to

haul it all away,” Jensen said with a laugh.

Foley, a member of the planning board in the 1960s,

said he remembers the gradual development of Oak Hill

as more and more businesses began to express interest in

Scarborough.

“It was a big boom time,” Foley said. “There was one

after another coming in and that’s when we first started

talking about how to be more efficient with land use.”

One of the major factors that led to economic

development of Scarborough was construction of

Interstate 295, which allowed greater access to the

once-remote town from Portland and other larger cities,

Jensen said.

“1-295 opened up Scarborough,” Jensen said. “We

were like way out in the country for Portland. People in

Portland had summer homes in Higgins Beach. That was

their idea of getting away from the city.”

Another major development came as business

expanded: More town residents.

“In my lifetime there has been a tremendous influx

of residential population,” Jensen said. “It kind of

went hand in hand with the decline of the farming and

agricultural bent that Scarborough had, and the move

toward being a bedroom community for a bigger general

business area.”

Jensen and Foley remember time with family was a

town value as they grew up.

“Back then a big thing for families to do on the

weekend was get in the car and drive down to Old

Orchard,” Foley said. “It seemed like a whole procedure.

You would drive down to Ken’s Place, place your order,

drive around Old Orchard looking at everything, drive

back, get your clams and then drive to the ice cream

stand.”

Francis Foley,

left, and his

son, Dick Foley,

keep a watch-

ful eye on the

ice cream ma-

chine at Foley’s

in the 1960s.

Dick Foley,

who operated

the business

with his sister

and brother

from 1963 until

1994, grew up

in the village of

Oak Hill. (Cour-

tesy photo)

After working at the ice cream stand for a few years,

Foley realized his family wasn’t the only one with the

tradition.

“I remember I used to see so much Ken’s stuff in my

trash barrels,” Foley said with a laugh. “I used to say,

‘thank you’.”

As time passed, and travel options increased, Foley said

more families began to leave town for extended stays

farther away from home.

“Now if somebody is going to take a vacation they have

to go to Aruba or something. It was very simplistic back

then,” Foley said.

Although no matter how hectic things got at the ice

cream stand, Foley said that there was always time for

family to come together.

“As busy as we were, every Sunday we would have

dinner as a family,” Foley said. “At the time I remember

we’d gripe about it, but when I look back on it now, those

were some of the best times I ever had.”

Although much has changed since the 1930s, Foley said

he still treasures the place he calls home.

“We’re very fortunate to have what we have,” Foley said.

“Scarborough is a nice town, both from an environmental

perspective and the type of building diversity we have

and I want people to enjoy it and protect it.”

Staff Writer Dan Aceto can be reached at 282-4337, ext.

237.

Black Point had ‘everything right there’

The inside of

Newcomb’s store

as it appeared in

Black Point during

the early 1900s.

The store was a

familiar spot for

local youth to find

work during sum-

mer months and

hitch a ride with

local farmers to

help pick berries

and perform odd

jobs around the

village. (Courtesy

photo)

Sixth in a series on the villages of Scarborough. Next

week: Prouts Neck.

By Dan Aceto

Staff Writer

For Mary Lello, life on the Newcomb family farm in the

1930s was quite the contrast from her peers at the other

end of Black Point Road.

“We were two miles apart, but it was like two different

worlds,” Lello said.

Lello, 89, and fellow Scarborough^ resident Daisy Higgins,

83, shared memories of growing up in the village of Black

Point for an archival interview that chronicles life in town.

Bruce Thurlow and Mary Pickard of the Scarborough

Historical Society led the project for the town’s next

landmark anniversary celebration.

Life in the 1930s often meant hard labor, and Lello was

no exception.

“There was a lot of work to do,” Lello said. ‘We were all

farmers down there.”

Her brothers helped out in the field and she worked with

her sisters in the kitchen.

Growing up on the farm brought responsibilities, even on

the daily commute to school.

“Sometimes when we drove to school we would deliver

milk along the way. We hoped it was good when we got

there,” Lello said with a laugh.

Summer brought more business opportunities for Lello

and other families.

Prouts Neck, a popular tourist destination, lured

travelers from near and far to enjoy local seafood and

scenic ocean views. While some travelers stayed in hotels,

those without accommodations found lodging in other

nearby places, including Black Point.

“People used to stay over like a bed and breakfast,” Lello

said. “It was amazing the difference in the summer. It was

a very busy time.”

Lello and her brothers and sisters would pitch in however

they could, from waiting tables to other chores for as many

as 10 guests at a time.

Some guests even became regulars.

“Most people came to the farm year after year and we got

to know some nice people,” Lello said.

Daisy Higgins, who lived on the opposite end of the village,

recalls Black Point as a village bustling with activity.

“We had everything right there in the community,”

Higgins said.

Higgins, who worked at the post office in Scarborough for

more than 37 years, remembers the area just across the

marsh from Oak Hill as a thriving community with two

general stores, a library, greenhouse, firehouse, state auto

garage, church and other amenities.

“It’s amazing how different our lives were in that one-

mile difference,” Higgins said.

Although some children may not have grown up tilling

soil and planting vegetables, many youth in Black Point

still experienced life on the farm.

At Newcomb’s store, local farmers would often park their

trucks and enlist help from children and teenagers to pick

berries and other fieldwork. The job may not have paid

much, but Higgins said it was an experience nonetheless.

“I may have got as much as 5 cents an hour,” Higgins said

with a laugh.

Higgins said many residents also tended land on the side

to grow their own food.

See BLACK POINT, page 5

Black Point————————————-

Continued from page 1

“It seemed that most everyone had a little farm,” Higgins

said,. “We used to grow green beans, potatoes and other

things in our backyard.”

By the 1950s, the landscape began to change as farmers

started selling land to developers for residential use.

Two decades later, the area once known for farming had

changed dramatically.

Many farms are gone, but Lello welcomes the renewed

interest in farming at Broadtum Farm and Frith Farm.

“It’s really wonderful that young people want to do

farming,” Lello said.

While many Black Point businesses catered to the needs

of locals, the village was bolstered by one of the largest

train stations in town.

“Many people would take mass transit, the train was a

big thing,” Higgins said.

Although the train may have brought many tourists to

the area, some used the service as a free lift from town to

town.

“The hobos would ride the freight trains and get off and

come knock on the door,” Higgins said. “My mother used

to tell us to come in the house, but she would give them a

sandwich or some coffee. A lot of people were out of work

during that time.”

If one thing unified each village in Scarborough, it was

the sense of community.

“We were free to do anything and it amazes me to this

day,” Higgins said. ‘We used to walk in the middle of

Highland Avenue or ride our bikes down to the beach and I

wouldn’t let my grandchildren do that now. We were pretty

free, but everybody knew everybody so that makes a lot of

difference.”

Among notable people who resided in Black Point was

Eldred Harmon, Scarborough’s first appointed fire chief,

who lived on a farm across from the fire station at the

comer of Black Point Road and Spurwink. He lived until

he was 99 and was known by many in town as a reputable

and hardworking individual, Thurlow said.

Although times were tough, many children found ways

to have fun with a limited budget. From swimming at

Foss Farm in the summer, now the sjte of Camp Ketcha,

to skiing down Fogg Road in wintertime and gatherings at

the Grange Hall, a little resourcefulness often went a long

way in the 1930s and 1940s.

“We were pretty sheltered, but I think it was a wonderful

time to grow up,” Lello said. “Kids today seem to be so

scheduled. When we had playtime, we went out and just

played ball and made up amusements, our own recreation.

I think we lived in a more relaxed time even though

everyone worked very hard.”

While the community atmosphere of the village life has

changed since the 1930s, Lello looks back on the time

she spent growing up with a fondness she always will

remember.

“We didn’t have any money but we had everything we

needed.”

Staff Writer Dan Aceto can be reached at 282-4337, ext.

237.

•q

Prouts Neck history features big hotels

Seventh in a series on the villages of Scarborough. Next

week: Spurwink.

By Dan Aceto

Staff Writer

Against the backdrop of a picturesque coastline made

famous by artist Winslow Homer, the Black Point Inn

on Prouts Neck is the last remnant of an era marked by

luxurious hotels and summer-long visitors.

“That’s the only hotel left now,” Elaine Killelea said.

“Everything else has changed.”

Killelea, 83, and others shared memories of growing up

in Prouts Neck for an archival interview that chronicles

development of Scarborough since the 1930s. Bruce

Thurlow and Mary Pickard of the Scarborough Historical

Society spearheaded the project.

Although the hotels may be long gone, Scarborough

resident Dorothy Hatch, 98, still remembers waiting

tables at the Checkley.

It was a beautiful place to work,” Hatch said.

The Checkley was one of seven large hotels that

included Atlantic House, Middle House, Jocelyn,

Cammock House, West Point House and Willows. They all

were known for catering to needs of affluent visitors, but

for Hatch, no establishment was finer than the Checkley.

“We thought we were superior to the Black Point Inn

because we had an elevator,” she said with a laugh.

Unlike today, visitors to Prouts Neck came by train to

A view of

Prouts Neck

from the

early 1900s

includes

three hotels,

from left,

Cammock

House, Mid-

dle House

and Willows.

The area

was once

the site of

seven large

hotels. (Cour-

tesy photo)

Scarborough and often stayed the entire summer, Killelea

said.

“People that came to Prouts Neck were very well-to-do

and would stay in big hotels for .months at a time. They

were not your general tourists,” Killelea said.

The influx of guests brought employment for many local

youths, eager to assist.

“It was a way that some of us picked up extra money for

school clothes and things,” Killelea said. “I remember the

boys would meet people at the trains and help them load

their trunks and deliver them to the hotels.”

Once vacationers arrived, there was plenty to do,

including golf.

“At one time there were about 20 caddies there at the

country club,” Killelea said.

Although waiting tables at the Checkley may have been

considered a summer job, the gig included a temporary

change of location and required staff to live all summer

in a dormitory attached to the hotel.

While the schedule may have been rigorous, there was

See PROUTS NECK, page 4

Page 4 Scarborough Leader August 5, 2011

Prouts Neck—————

Continued from page 1

downtime, Hatch said.

From stealing away to go to the beach,

singing in the garden or mischievously

sneaking around the hotel at night and

causing trouble with the bellhops, there

was always fun to be had, Hatch said.

“We all seemed to have a good time. It

was like us against the world over there,”

Hatch said.

Scarborough youth also found work in

the area at the general store and grocery,

V.T. Shaw’s.

“Almost every youngster worked there

growing up,” Killelea said.

The store even catered to the specific

needs of vacationing visitors by taking

individual orders for grocery items and

other supplies.

“They went to every single house on

Prouts Neck and took orders in the

morning and came back in the early

afternoon from Portland,” Killelea said.

After World War II and the advent of

the automobile, many people opted to go

to larger stores in favor of local markets,

Killelea said.

“When supermarkets came in people no

longer wanted to shop from local stores

and pay local prices,” Killelea said. “People

began to drive their own cars and that

changed many things.”

As the years passed, many longtime

visitors to the neck settled in the area and

eventually bought land and built cottages

of their own, Killelea said. Over time, as

more and more people sought regular

employment in Portland and other bigger

cities, work at the hotels became harder to

find. A gradual decline began in the 1940

and after World War II, the area changed

dramatically, Killelea said.

Despite the influx of summer visitors,

there was little that could stop Killelea

and others from enjoying themselves in

the village. From riding her bike along

the boardwalk in the bird sanctuary to ski

jumping off the boathouse on Ferry Beach,

life couldn’t get any better as a youth.

“It was a marvelous place to grow up,”

Killelea said. “We had beaches, a yacht

club, a golf course, a pond for skating in

winter, things they (visitors) didn’t even

see.”

And if any child ever acted out,

neighbors were more than welcome to tell

children how they ought to behave.

“Every adult felt perfectly free to tell you

(you were misbehaving),” Killelea said.

“Everybody in the neighborhood was a

caretaker and caregiver.”

That didn’t stop Killelea and others from

enjoying themselves.

“It was such a safe and wonderful time

around here,” Killelea said. “It was a time

of friendliness, wanton friendliness.”

Even during Prohibition, the fun never

stopped.

“I remember my father and uncles

brought liquor into Prouts Neck,” Killelea

said. “They would come in the winter and

wait a little bit until the one police officer

went to bed and then in came these people

with their liquor. Prouts Neck always had

their liquor, even during dry times.”

And some of that liquor was quite

notorious, including a recipe formulated

by Winslow Homer’s brother, Arthur,

simply known as “Daddy Homer’s Punch,”

a favorite among locals during Fourth of

July celebrations.

Dorothy Hatch reminisces about her

time as a waitress at the Checkley ho-

tel in Prouts Neck. Hatch, 98, worked at

the hotel during the 1930s. (Dan Aceto

photo)

“I remember having a glass; boy that

punch was strong,” longtime Scarborough

resident Maude Libby said with a laugh.

No matter where children were, they

knew when to come home for supper.

“When you could smell the wood smoke

you knew it was time to get going,”

Killelea said.

Like other villages in Scarborough,

Prouts Neck and Black Point were home

to a one-room schoolhouse, the Black

Point School. Although there may have

been only 25 students, the teacher faced

staggering responsibilities, Killelea said.

“Sometimes the teacher taught all eight

grades, I don’t know how they did it,”

Killelea said.

Killelea said making the transition

to Oak Hill Grammar School just a few

years later and meeting children from

other villages for the first time was quite

a shock.

“It was terrifying, it really was,” Killelea

said. “It was before we had a school bus, so

we had to walk as well.”

Though activity in the remote area

of Prouts Neck remained fairly calm

throughout the years, one event left a

lasting impact on Killelea: The wreck of

the freighter Sagamore.

The Sagamore, en route from Portland

to New York, capsized Jan. 14, 1934, after

hitting Corwin Rock off Prouts Neck.

The freighter was filled with wool that

was quickly saved by local residents, said

Killelea. She remembers watching the

scene from a bonfire on nearby rocks.

“All the people in town went out and

rescued things. Nobody lost their lives and

they rescued some very wonderful wool,”

Killelea said. “Everyone in town was

wearing snowsuits from the Sagamore

that winter.”

Killela said the memory of her father

rowing out to the wreckage frightened her

and her mother because he couldn’t swim.

“Most men were fishermen, but not

many could swim,” Killelea said. “It was

just one of those things. No fishermen ever

learned how to swim.”

Although times may have been hard for

many in the area, Killelea remembers

the beauty of growing up in a time when

things were simpler.

“I’m sure none of us had a great deal of

money, but we didn’t know it,” Killelea

said. “We had everything we needed and it

was a fun and wonderful time to grow up.”

Staff Writer Dan Aceto can be reached at

282-4337, ext. 237.

Farms dominated Spurwink landscape

Eighth in a series on the villages of Scarborough. Next

week: Higgins Beach.

By Dan Aceto

Staff Writer

Ralph Lorfano remembers a time when his entire

Scarborough neighborhood was devoted to the land.

“Back then it was really all farming,” Lorfano said. “It

pretty much took up the entire road.”

Earlier this year, Lorfano, 77, was among residents

interviewed for an ongoing series that chronicles the

history of Scarborough villages. Bruce Thurlow and Mary

Pickard of the Scarborough Historical Society spearheaded

the project.

Although Spurwink may not have been a traditional

village with a garage and town center like Dunstan and

Oak Hill, it still had a strong sense of community.

“All of the farms worked together and knew each other,”

Thurlow said. “They weren’t competitors, they were all

friends.”

From lettuce to strawberries and every kind of vegetable

The Spur-

wink Country

Kitchen as

it appeared

in 1960. The

restaurant is

still a popular

spot for local

residents.

(Courtesy

photo)

in between, Lorfano said demand for produce in the 1930s picked their crops — it had only just begun,

and 1940s was so great that large trucks stopped by twice “There were some farmers who would drive down to

a day to collect and ship food to markets.

Work didn’t stop at the end of the day other farmers See SPURWINK, page 5

Spurwink————————–

Continued from page 1

Boston six times a week in the summer,”

Lorfano said.

Even the experience of going to market

in Portland was something to behold, he

added.

“The minute you landed there were

people right there,” Lorfano said. “You’d

turn around to weigh something and they’d

be piling zucchinis on the scale and putting

things in bags. It was absolutely wild for

the first hour.”

While work was plentiful, wages were

modest, Lorfano said.

“In 1938 I remember there was a man

who worked for one dollar a day,” Lorfano.

“It was during the Depression and people

were looking for work. I remember the year

before he worked for 50 cents.”

Although Lorfano admits the hours were

long, there was still time to enjoy life.

“We used to always say, “When we’re

done with this lettuce patch can we go

swimming?’ And we’d go down to the river

for a little while and come back,” Lorfano

said. “It was hard work, but we still had

fun.”

From playing in the ham to climbing

trees, there was always something to do,

including sledding in the middle of the

street.

“We used to sled in the middle of the

roads, and when they’d come by to sand

we would always yell at them,” Lorfano

said with a laugh. “We didn’t really leave

Spurwink much.”

Going to school in the 1940s, Lorfano

remembers the stark difference in

transportation.

The Stanford family farm as it appeared in the

early 1900s. George Stanford, left, holds a pair of

pheasants after a hunting trip in the 1950s. Stan-

ford owned a contracting business and farm on

Spurwink Road. He regularly sold produce such as

lettuce and strawberries to markets in Boston and

Portland. The Stanford farm was one of many that

once dominated the Spurwink landscape. During

the 1960s and 1970s many farmers sold their land

for residential use, which dramatically changed

the landscape and occupations for many in the

area. (Courtesy photos)

CHECKOUT

See SPURWINK, page 6

Spurwink—————————————

Continued from page 5

“They used to pick all the kids in Scarborough up on one

bus,” Lorfano said. “That’s quite the big change. The kids

from North Scarborough had a long day; they would be

picked up first and dropped off last.”

Among notable places in the area was local favorite

Spurwink Country Kitchen, a home-style restaurant that

still exists today.

Farming wasn’t the only occupation for Lorfano’s family

and others: They also catered to summer residents on

Prouts Neck.

Lorfano’s uncle, George Stanford, was well known

throughout Scarborough. He ran a contracting business

in addition to farming and did a variety of work for town

residents, including making cabinets. He also held spare

keys in case visitors were locked out of their summer

cabins.

While farming boomed in the early 1900s, life in

Scarborough began to change in the late 1960s and 1970s,

Lorfano said. As the value of land increased, younger

generations lost interest in farming and many sold

property for residential development.

The loss of farms dramatically changed the landscape

and culture of Scarborough.

“Now there’s none left on Spurwink,” Lorfano said. “It’s

sad to see it disappear.”

The sense of community also began to fade as

Scarborough’s population increased, Lorfano said.

“Back then everybody knew everyone else,” Lorfano

said. “It’s quite a bit different now; sometimes you don’t

even know your neighbors. Things were much more low

key. It’s just such a hustle-bustle today with everything

computerized. You very rarely get to talk to anybody on

the phone anymore.”

George Stan-

ford, front

center, with a

work crew at

his farm dur-

ing the 1950s.

Stanford, who

owned a farm

and contract-

ing business

in the area,

employed many

local youth,

including Ralph

Lorfano, seated

at front right.

Lorfano began

working at the

farm when he

was 10. (Cour-

tesy photo)

While much of the landscape of Spurwink may have food.”

changed over time, Lorfano plans to continue doing what

he loves most: Gardening. Staff Writer Dan Aceto can be reached at 282-4337, ext.

“I don’t know what I’d do if I wasn’t able to grow a little 237.

Residents recall bonds of summer

Ninth in a series on the villages of Scarborough. Next

week. Pleasant Hill.

By Dan Aceto

Staff Writer

Looking back on his time growing up at Higgins Beach,

Andy Putney recalls the joy he felt each summer when

his friends from afar came back to town.

“I remember how exciting it was in the spring to come

back to Higgins Beach because almost 90 percent of the

people coming in were simply summer residents,” Putney

said. “They were my summer friends, but we had a bond.”

Putney was among residents interviewed for an

archival discussion this year that chronicles the history

of the villages of Scarborough. Bruce Thurlow and

Mary Pickard of the Scarborough Historical Society

spearheaded the project.

See HIGGINS BEACH, page 5

The Breakers

Inn as it ap-

pears today at

Higgins Beach.

The inn, built

as a private

home in 1900,

has been

owned and

operated by

the Laughton

family since

1956. (Courtesy

photo)

Higgins Beach————————————–

Continued from page 5

the way across the cliffs and sneak into the pool at the

Black Point Inn,” Martin said with a laugh.

While the Black Point Inn provided a welcome change

from chilly water’s of the Atlantic, locals had another

favorite swimming hole: The Spurwink River. Even

its location next to the town sewer outlet did little to

dissuade children from enjoying an afternoon swim.

“We used to like to go to the river because you could run

and dive in, but you had to go when it was high tide and

only when it was coming in because of what was going

out,” Martin said with a laugh. “My father used to always

say, ‘don’t open your eyes when you dive in!’”

Questionable soil along the river also provided another

form of entertainment, spid David Brookes.

‘We used to clam in those flats!” Brookes said with a

laugh. “But here we are, all alive today.”

While the allure of freshly shucked Scarborough clams

was tempting, youngsters had other opportunities

for nourishment when hunger struck, including the

Lunchbox, a local hot dog stand.

“That was a big deal, bringing bottles up to the

Lunchbox,” Johnson said.

Some children were more honest than others about

where they got their secondhand loot.

“I remember there were some who would go around

the back of the store and pick up bottles and bring them

around to the front,” Brookes said.

Although returning bottles was an accepted form of

currency at the Lunchbox, area youth also made money

doing odd jobs in the neighborhood, including shoveling

driveways and other tasks.

For the truly ambitious, there was always the option of

being a “pin boy” at the local bowling alley, the Pliggins

Beach Pavilion.

The job of setting and resetting pins might have

sounded innocent enough, but the task was easier said

than done.

“You got the feeling they weren’t bowling for the pins,

they were bowling for you,” Brookes said with a laugh.

Johnson and others who took on the job had one simple

strategy to make it through a day of work: get out of the

way.

“There used to be a bench you could sit on, but once you

knew there was someone really chucking ’em down there,

you would stand right up,” Johnson said.

Dangerous as it may have been, the alley and an

adjoining store, Stratford Farms, were local favorites. The

store featured an ornate soda fountain made of brass and

marble.

“That was the place to go,” Johnson said.

The building is long gone, but the soda fountain is still

in use today – albeit for a much different purpose.

“My father bought the soda fountain and broke it up for

marble,” Laughton said. “It’s now the pastry counter that

I make pies on in the kitchen.”

The building also hosted movies and dances on a second

floor and was integral to the village for another reason: It

was one of the few places that had a phone.

“People with relatives would call the store and someone

would run down and find the family that was being called

and somehow make contact,” Brookes said.

One of the more peculiar services offered to beach

residents was Albert Coppola’s aerial spraying service

in Scarborough called New England Aerial Spray. He

would fly over Higgins Beach and spray DDT to ward off

mosquitoes in the area.

For those who were traveling to the beach on vacation,

the event could be quite startling.

“People from away didn’t know what that meant, but

they found out soon enough,” Johnson said.

“He would take the plane and circle a couple of times

and that was the signal that if you didn’t want your car

plastered with DDT to move it away,” Laughton said.

“He’d spray it all over everything and that would knock

the mosquitoes down for a couple of days.

The quaintness of the village is what many residents,

including Laughton, remember. From local fishermen

selling the day’s catch or blocks of ice to name signs

instead of numbers on cottages, there was always a sense

of community in the village.

Laughton, whose family has owned and operated the

Breakers Inn at Higgins Beach since 1953, said one of

the biggest changes to the area was development of the

village away from the familial feel it once held.

“Higgins Beach has become a much more upscale

community now,” Laughton said. “There are fewer

families there with small kids.”

Johnson said he has three simple words for future

generations of visitors to the beachside community.

“Sustain Higgins Beach.”

Staff Writer Dan Aceto can be reached at 282-4337, ext.

237.

Nonesuch

Books & Cards

Locally Owned Full Service Bookstores

Make Nonesuch Your Bookstore!

Higgins Beach

Continued from page 1

While Higgins Beach may have

traditionally been a summer getaway for

families from Canada and other parts of

New England in the early 1900s, the area

always harbored a close-knit atmosphere.

Changing seasons brought great

anticipation of coming guests for those

who lived year-round by the beach.

“All my friends were from away,” Brad

Johnson said. “People would come in and

rent cottages for the summer, then it was

a month, then two weeks, which you even

rarely see now.”

Putney and his friends always found

adventures, even without a car.

“In the old days we never used the

streets because there were always

unwritten right-of-ways between the

properties,” Putney said.

That familiarity lent itself to the rocky

shoreline as well.

“It was like a route, you knew where the

natural places to climb the rocks were,”

Johnson said.

The area further down the beach also

provided great opportunities for Rodney

Laughton and other Scarborough children

to steal away and skip rocks, collect sea

glass and enjoy time away from authority

figures.

“It was a great place to escape adult

supervision and spend a couple of hours

on a Sunday afternoon,” Laughton said.

Some, like Scarborough resident Connie

A 1910 photo of Higgins Beach shows the Silver Sands Inn, a popular destination for summer visitors, far right. The inn

was destroyed in the blizzard of 1978. (Courtesy photo)

Martin, even braved the journey along the

shoreline all the way to Prouts Neck.

“Our challenge every year was to get all

See HIGGINS BEACH, page 7

Village view

Plenty of work and play in Pleasant Hill

Last in a 10-part series on the villages of

Scarborough.

By Dan Aceto

Staff Writer

Pleasant Hill, located at the four-way

intersection where Highland Avenue

joins Scarborough from South Portland,

has seen many changes from a once rural

farming community to flourishing suburb.

Elwood Willey, of Walpole, Mass., says

times have changed but he’ll never lose

memories of growing up and working on

the farm to make a living.

“In the 1940s and 1950s it was indeed

a pleasant place for a young farm

boy to grow up and roam around the

neighborhood,” Willey said. “Today that

more carefree, rural farming environment

and culture seems like light years away

compared to today’s cheek-by-jowl houses

built on disappearing farm land, the busy

and noisy roads, and the hectic, fast-

paced, bedroom community way of living.”

Willey, 73, was interviewed this year as

part of an ongoing series that chronicles

the history of the villages of Scarborough

from the 1930s. Bruce Thurlow and Mary

Pickard of Scarborough Historical Society

spearheaded the project.