Page 3 of 4

Text by Mary B. Pickard

The Twentieth Century

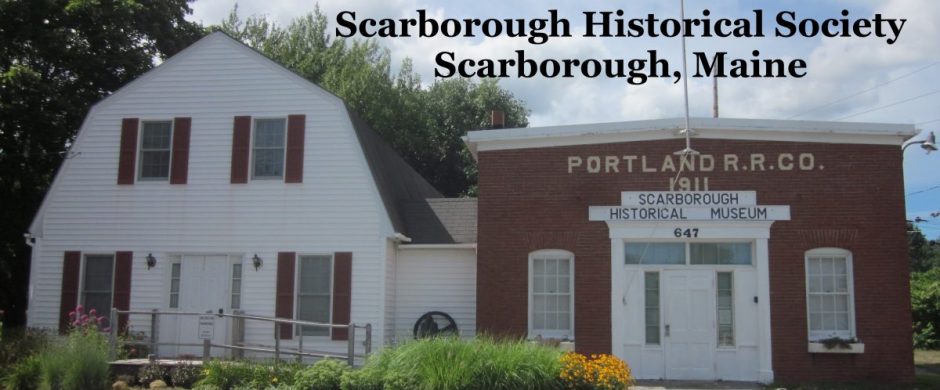

By 1902 Scarborough had electricity, and electric cars (trolleys) replaced horsecars. There was great excitement that July when the rails of the Biddeford and Saco Railroad Company were finally connected to those of the Portland Railroad Company, connecting South Portland to Saco and providing trolley service through Scarborough. In the heyday of the trolley, one could travel south as far as Philadelphia or north to Bangor and beyond using connecting lines. By the late 1920s rising costs and declining business caused the phasing out of the trolleys. The last trolley ran through Scarborough in 1932.

As the use of trolleys declined, use of automobiles became more widespread. Automobiles had begun to appear in Scarborough in the early 1900s, but road conditions were so poor that use was essentially seasonal. Even as roads began to improve in the 1930s, farmers would keep a horse and wagon as backup.

Aviation fever came to Scarborough in 1926 when Chester Jordan and Phillips Payson purchased land for an airport off Manson Libby Road. Construction began in 1927 and was completed in September 1928. During its period of operation, famous people who landed at the Scarborough airport were Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart and Wiley Post. Within ten years, the airport became inadequate for the increasingly larger and more powerful aircraft and airport operations moved to Stroudwater. The Scarborough complex became a flying school and air show site, but it shut down completely in the 1950s. The site is now home to the Scarborough Industrial Park. A second airport, the Port-of-Maine Airport, opened after World War II at a site off Pleasant Hill Road. Service operations and flying schools operated at Port-of-Maine until the 1960s.

Trolleys, trains and automobiles brought tourists to Scarborough. Shore dinner places, such as the Dunscroft and Wayland, tourist cabins and lodging houses attracted motorists; and large guest hotels on the coast, such as the Checkley and Atlantic House, lured tourists who often arrived by train from Boston, New York, Montreal and beyond. Set back on Route 1 not far from the Willowdale area was the Danish Village, an authentic copy of the Danish village Ribe. It was a unique, one-hundred-unit pre-motel, a connected series of units that would later be typical of the modern motel. It ceased operation as a motor court with the advent of World War II and gas rationing, and the Government converted the units to housing for South Portland shipyard workers.

During World War II, Scarborough residents were involved on the warfront as well as the homefront. At home some worked on Liberty ships at the shipyard in South Portland. Frances Libbey, a Scarborough teacher, wrote to local servicemen and women–well over one hundred. Her chatty letters full of local news provided a valuable link to home. A group of civilians known as the Ground Observer Corps watched the skies for enemy aircraft and then again during the Cold War of the 1950s. The organization disbanded by 1959 when advanced radar systems made the Ground Observer Corps obsolete.

The 1950s brought change as veterans returned home, married, built houses and became involved in the community. The Maine Turnpike opened in 1948, bringing business to Scarborough. Population grew as people moved to town to fill jobs created by commercial growth. Although an era of peace, conflicts in Korea and Vietnam involved Scarborough men and women. The 1960s and 1970s were a traumatic time, as increased use of television brought world events into everyone’s living room: the assassination of President Kennedy; the civil rights movement; the equal rights movement for women; Neil Armstrong’s walk on the moon; and the continuing Viet Nam struggle.

During the last two decades, Scarborough continued to grow. Housing developments sprang up; large retailers Wal-Mart and Sam’s Club came to town; Maine Medical Center broke ground for a complex of medical offices and lab, and the town built new support services for the burgeoning population. Fortunately, some Scarborough residents realized the need to protect the natural resources that had attracted people to the town. Two groups, the Scarborough Land Conservation Trust and the Friends of the Scarborough Marsh, formed to safeguard the town’s open space, marshland and nature trails for future generations.