Catch of the Day – Part 4

By Bruce Thurlow

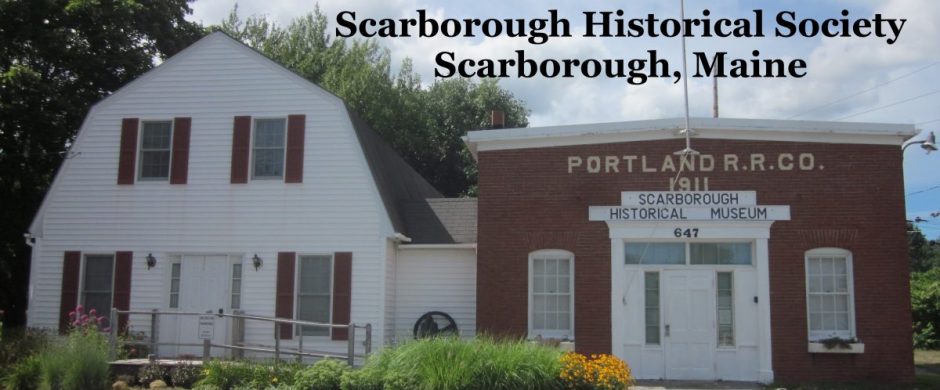

Images from Scarborough Historical Society, Bruce Thurlow, Bill Bayley and Don Googins

I Remember Lobster Fishing in Scarborough

Most clam and lobster fisheries in Scarborough have been associated with Pine Point, and many Pine Point residents have been lobstermen, clam diggers or both. The Scarborough anchorage at Pine Point is where the Scarborough, Nonesuch and Libby Rivers converge and the departure point for many fishermen. As one of four boys whose father, grandfathers, several uncles and cousins were all lobstermen, I recall lobster fishing during the period 1949 to 1966.

Anchorage at Pine Point

In the mid-1900s, Scarborough lobster fishermen set strings of traps that were checked, as weather permitted, on a daily basis. Occasionally, when winter fishing or fishing in very deep water, one line had two traps (doubles); but most of the time only single traps were on a rope and buoy (singletons). Men would set a string of singletons, anywhere from 4 to 8 or 20 to 40, depending on the bottom to be fished. Each trap was connected to a buoy by a rope about 15 fathoms in length. About 5 fathoms up from the trap, a bobber was attached to the rope. This was intended to prevent the rope from getting caught on ledges, kelp, or anything else at low tide.

Around 1952, some fishermen began using fathometers to check the water depth and ocean floor. Before fathometers, lobstermen used greased window weights attached to twine to do this. Fishermen also used visual signs to note where to put a string of traps. For example, it was quite common to hear “dump the string” when the stern came between those two large trees on Stratton Island.

It was understood that two territories existed off Pine Point. A lobster fisherman would either go to Stratton and Bluff Islands or along Prouts Neck to Richmond Island. Fishermen who went toward Richmond Island stopped at a place called Deep Ledge and those from the Spurwink River would fish along that part of the Cape Elizabeth coast as far as and including Richmond Island. Those who went to Stratton and Bluff Islands would often go toward Old Orchard Pier. However, they would not fish any of the islands found at the Saco River entrance, for these were the grounds of Saco (Camp Ellis) fishermen.

These historic community boundaries are still respected, and many young fishermen might fish where family before him fished, but today anyone goes anywhere. Yet, many places along Maine’s coast still have definite territories. Recently, the press has had stories related to a shooting and boats being sunk over territorial disputes! A reason for the local decline in observing territories, I speculate, is that many fishermen are going offshore. Larger fiberglass boats; more powerful diesel engines; and modern equipment, such as hydraulic pot haulers, GPS, radar, etc., enable the lobster fisherman to reach offshore fishing areas faster and more safely.

Today, many lobster fishermen do go to offshore grounds. However, most lobsters are caught in late summer and fall when they migrate closer to shore areas to molt. This is when a lobster sheds its exoskeleton and grows a new shell. During this period lobsters are very soft, don’t move around much for several days and are vulnerable to almost everything, including fish and seals. Once lobsters become more active, they are very hungry and are caught in higher numbers.

Bayley’s Lobster Pound was the dealer for most Pine Point and Ferry Beach lobster fishermen. Bayley’s shipped lobsters to the Fulton Fish Market in New York City and provided lobster meat to many Old Orchard Beach, Saco and Scarborough restaurants and area take-out establishments. Other Pine Point lobster pound dealers have been Googin’s Lobster Pound, Fogg’s Lobster Pound, Thurlow’s Shellfish (formerly Googin’s Lobster Pound), Pine Point Seafood Distributors and the Fishermen’s Co-Operative. Today some lobster fishermen are selling lobsters from their homes. An ability to have a saltwater tank away from the source of the water has enabled these men to have a home business. In 2010 the only Pine Point-based lobster dealers are Bayley’s Lobster Pound and the Fishermen’s Co-Operative.

Managing the Catch

Bayley’s Lobster Pound, Scarborough, ca. 1948

Since all lobsters look alike whether caught near shore or offshore, it’s imperative that state, interstate and federal regulations complement one another. The Maine Department of Marine Resources manages lobster fishing within a three-mile boundary of the coast, working closely with the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, a compact of fifteen eastern seaboard states. Federal regulations are covered under the auspices of the National Marine Fisheries Service and are concerned with lobster harvesting between three and 200 miles offshore. All states and the federal government share a minimum legal size, 3 ¼ inches carapace-length measured from the eye socket to the beginning of the tail. Maine has a maximum legal size of 5 inches carapace-length, to keep the largest breeders in the lobster population. All egg-bearing females and those with a V-notch cut in a tail flipper must be released. Cutting a V-notch is meant to keep the females in the breeding pool and is voluntary on the part of conservation-minded lobstermen.

Sources

Milliken, John, et al. petitioned the 59th Legislature of Maine to abrogate previous legislative act allowing existence of the Southgate Diking Company.

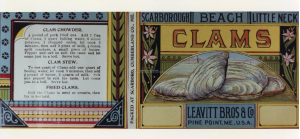

Scarborough Historical Society Collection: Clamming

Thurlow, Bruce. Presentation to the Scarborough Historical Society. Lobster Fishing at Pine Point from 1940-1970.

Thurlow, Bruce. Recollections About Lobster Fishing. Unpublished. Written for his sons, 2008.