Left to Right Front Row

Percy Nichols, Roger Saywood, Donald Fredericks, Edward Meserve Jr., Donald Richardson, Wade Harmon, Clayton Skillings.

Second Row

Isabelle Harmon, Marguerite Skillings, Betty Brimson, Shirley Libby, Beverly Meserve, Frances Burnson, Deloris Harmon, Eva Swinborn

Third Row

Miss Jane Field, Teacher, Hardley Hicks, Harold Richardson, Leon Skillings, Guy Pillsbury, Alfred Swinborn, Frederick Newcomb.

Fourth Row

Mary Chase, Edith Nichold, Ellen Chase, Loretta Arcuambault, Jane Skillings, Mary Newcomb.

Back Row

Granville Pence, Edward Meserve, Jr., Norman Harmon.

Note

There were two different students with the name Edward Meserve in this class. One was a Jr (son of Edward Meserve) the other was the son of George Meserve.

Source:

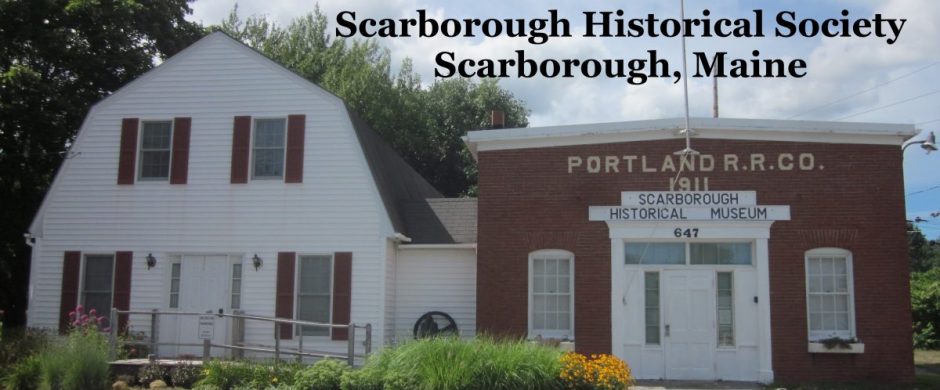

Scarborough Historical Society

Newcomb Collection #84.4.6

(Photo Box 3 – File: Black Point School )